A Timeline of Erasure and Reclaiming

Egypt’s African Empire (2700–1070 BCE)

Across the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, Egypt ruled lands reaching deep into Nubia and far north through Sinai into Canaan. Temples, governors, and trade routes tied everything from the Nile to the Levant under African control. The lands that would later be called Israel and Palestine were African-ruled for almost two thousand years.

Greek Witness (5th–4th centuries BCE)

Greek historians like Herodotus and philosophers like Aristotle described Egyptians and Ethiopians as dark-skinned peoples, confirming that the world saw Egypt as part of Africa and its people as Black. Classical testimony left no ambiguity about Egypt’s African identity.

Medieval Maps and the Unified Worldview (7th–14th centuries CE)

European T-and-O maps, including the Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300), divided the earth into Africa, Europe, and Asia meeting at Jerusalem. These medieval depictions kept the Holy Land tied to Africa, with no separation between African and Levantine soil.

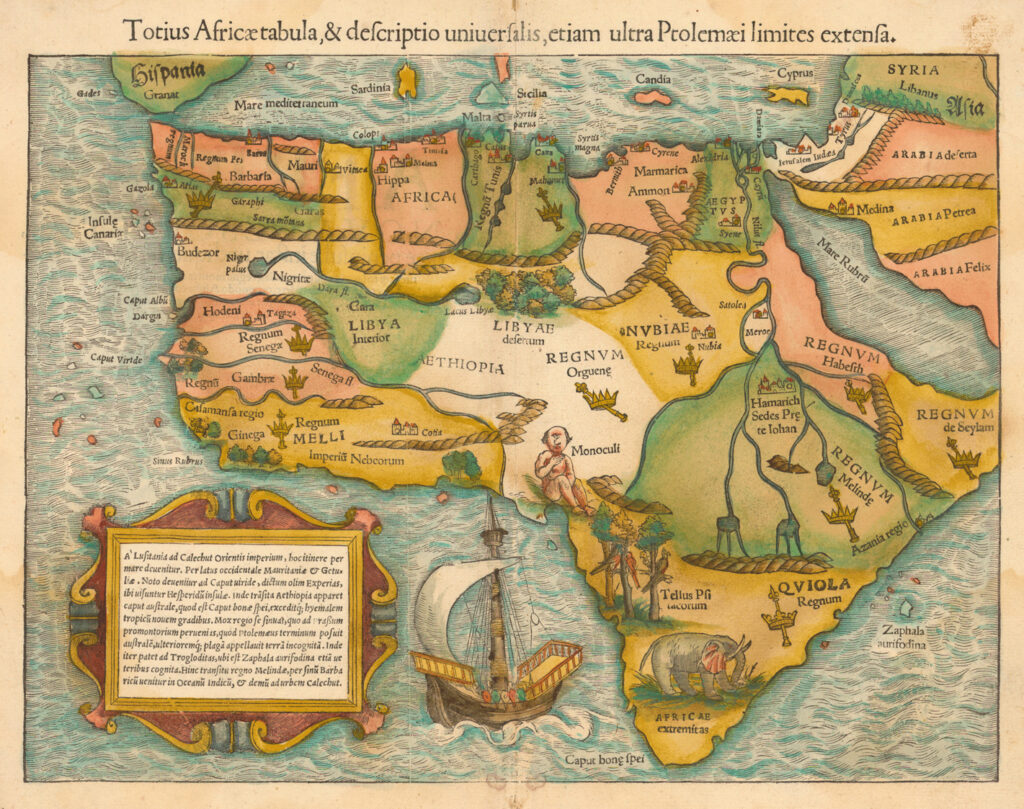

Renaissance Mapping of Africa (1540 CE)

Sebastian Münster’s Africae Tabula Nova defined Africa broadly. Regions near today’s Holy Land appeared within Africa’s frame, showing that early modern cartographers still treated that geography as African territory, not Asian.

Negroland and the Kingdom of Juda (1747 CE)

Jean Baptiste d’Anville’s Map of Negroland marked a Kingdom of Juda along the West African coast, visually tying West Africa to ancient Hebrew heritage. The cartographic link reinforced African claims to biblical ancestry.

Olaudah Equiano’s Testimony (1789 CE)

In The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, the Igbo abolitionist described his people’s practices of circumcision, purification, and dietary laws as identical to Hebrew customs, asserting that Africans descended from the ancient Israelites.

Africa’s Boundaries Before Colonization (1822 CE)

Early nineteenth-century maps like Morse’s Africa continued to include the Holy Land inside the African continental frame. The African context of Jerusalem remained normal cartography before Western imperial powers intervened.

The Colonial Rebrand: “Middle East” (1850s–1902 CE)

British officials first used “Middle East” while administering India in the mid-nineteenth century. U.S. naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan popularized it in 1902. The label was a geopolitical invention that shifted sacred geography out of Africa and into a newly imagined “Asia Minor” to suit colonial strategy.

The Suez Canal and the Great Divide (1869 CE)

When Europeans carved the Suez Canal through Egypt, they physically and symbolically sliced Africa apart. Within decades, European atlases redrew boundaries excluding the Holy Land from Africa—an act of political geography that served empire, not truth.

European Jewish Migration to Palestine (1881–1914 CE)

The first large wave of European, primarily Russian and Eastern European, Jews began moving into Palestine during what became known as the First Aliyah (1881–1903). They were fleeing pogroms and persecution in the Russian Empire. A second wave, the Second Aliyah (1904–1914), brought thousands more settlers influenced by early Zionist ideology.

Zionism and the Political Foundation (1890s–1940s CE)

Modern Zionism emerged in Europe in the late 19th century. Nathan Birnbaum coined the term “Zionism” in 1890, and Theodor Herzl organized the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897, establishing the World Zionist Organization. European political lobbying for a Jewish homeland intensified under British protection during and after World War I, especially after the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

Institutionalizing the “Middle East” (1930s–1940s CE)

During World War II, Britain and the United States formalized the term in military and diplomatic usage. Western cartography finished the separation: Jerusalem and the surrounding lands were officially detached from Africa.

The State of Israel (1948 CE)

Following British withdrawal from Palestine, the Zionist leadership declared the creation of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948. The declaration came less than eighty years after the first Russian settlers began arriving. It was recognized by the United States and the Soviet Union within days, cementing a new geopolitical order rooted in European colonial restructuring.

Geological Truth: The African Plate (20th Century–Present)

Modern tectonic studies confirm that Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and western Jordan lie on the African Plate, not the Asian one. The Dead Sea Transform marks the boundary where the African and Arabian plates meet. The land called “the Middle East” literally rests on African ground.

Conclusion

For millennia the Holy Land was African in rule, culture, and even bedrock. Only in the past century and a half did Western powers redraw it for colonial convenience. The language of the “Middle East,” the creation of Israel, and the borders that followed were inventions serving empire. The earth itself—through its tectonic plates—still tells the original story: the Holy Land remains African.

Key Sources

Herodotus, Histories, Book II

Aristotle, Physiognomonica

Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300 CE), Hereford Cathedral

Sebastian Münster, Africae Tabula Nova (1540 CE)

Jean Baptiste d’Anville, Map of Negroland and the Guinea Coast (1747 CE)

Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789 CE)

Alfred Thayer Mahan, “The Persian Gulf and International Relations,” National Review (1902)

United States Geological Survey: “African Plate” and “Dead Sea Transform” pages

U.S. State Department Archives, 1940s wartime “Middle East Command” records

First and Second Aliyah records (1881–1914)

Theodor Herzl, Der Judenstaat (1896)

Balfour Declaration (1917)

United Nations Resolution 181 (1947)